China’s public worries pointlessly about GM food

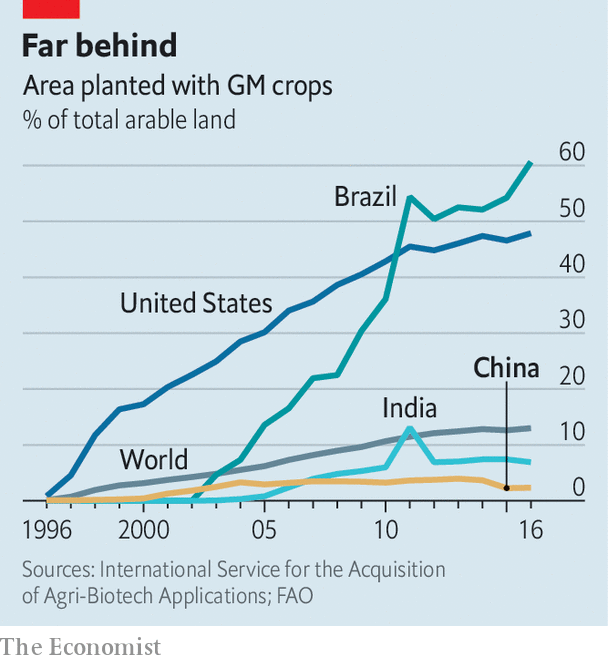

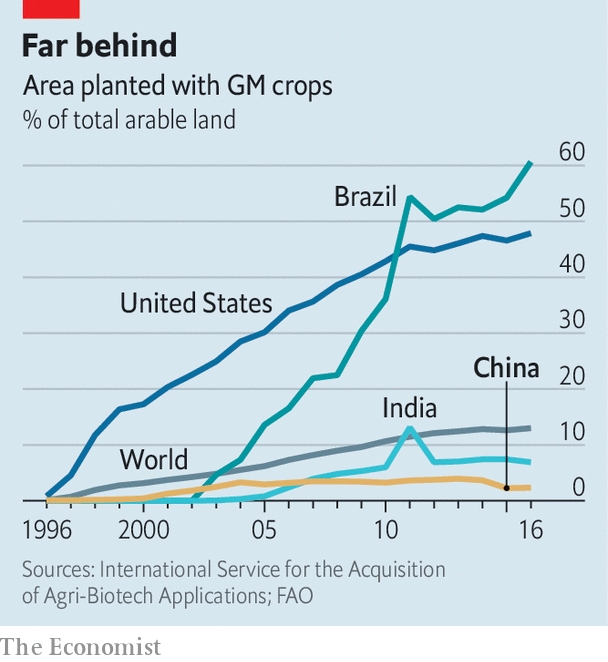

AMID AN ESCALATING trade war with America, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has tried to reassure a nervous public by insisting that his country can go it alone in its pursuit of tech supremacy. The Chinese people must “cast aside illusions and rely on ourselves”, he said in April soon after the first shots were fired. But in one technological realm, China appears less eager to surpass America: the development of genetically modified (GM) food crops. China was once a world leader in the field, but in the face of public opposition it now lags far behind (see chart). Unlike America, China restricts the commercial use of GM strains largely to non-food farming.

In 2016, after years of vacillation, the government looked ready to allow wider introduction of GM food crops. In a five-year planning document, released that year, it said that certain GM maize and soyabean varieties would be in commercial use by the end of the decade (an experiment with GM rice is pictured). But it has yet to convince the public to swallow the idea. A study published this year on the website of Nature, a British science journal, found that just over one in ten of respondents to a survey in China had a positive view of GM food. More than 45% were opposed to it. Only about 12% said they trusted information on the topic provided by their own government. Fewer than one-quarter said they had faith in scientists’ views. Nearly one in seven believed GM technology to be “a form of bioterrorism targeted at China”.

Anxieties show no sign of abating. Indeed, one of the most high-profile campaigners against GM foods has recently gained even greater prominence (and public admiration) thanks to his involvement in exposing a celebrity scandal that has nothing to do with food. In May Cui Yongyuan, who achieved fame in the 1990s as a presenter on state television and later as a flame-throwing blogger, posted to his nearly 18m followers on Weibo, a social-media site, accusations that Fan Bingbing, one of China’s best-known actors, had misdeclared her income to the tax authorities. For most of the summer Ms Fan disappeared from public view, apparently into some form of custody. She emerged in October with an abject apology to the public and promising to pay 884m yuan ($127m) in fines and back taxes. People are still avidly gossiping about the case.

Cao Cong of the University of Nottingham, the author of a new book about GM crops in China, says Mr Cui has been the most influential critic of the technology. There is also a more organised force at work. A coterie of diehard Maoists and neo-leftists oppose GM foods partly because of concern about food safety but mainly because they fear that foreigners, especially Americans, will use their mastery of genetic engineering to gain control of China’s food supply. The trade war launched by Donald Trump will fuel their conspiracy theories. In tacit recognition of the leftists’ appeal, especially to society’s underdogs, Mr Xi himself uses strikingly Maoist rhetoric. Five years ago he urged “bold” competition with foreign developers of GM crops. But since then he has kept quiet on the topic.

People in other parts of the world have been munching GM crops for a quarter-century without ill effects. GM techniques can raise farm output and reduce the use of pesticides. The overwhelming scientific consensus is that they are safe. But in China many unrelated safety scandals have sapped public confidence in the authorities’ ability to regulate such things. On October 16th the government imposed a $1.3bn fine on a company that had given dodgy vaccines to hundreds of thousands of children. Many people still shudder at the discovery in 2008 that thousands of children had been hospitalised after consuming tainted milk products. The government’s anxiety about the strength of public dissatisfaction is reflected in omnipresent slogans in city streets about the need for strict supervision of food safety.

James Chen, chief executive of Origin Agritech, a firm based in Beijing, says that public opinion may complicate his business plans. One of his company’s products is a GM maize seed that long ago received official safety approval. “We saw a growing focus on GM within the government and we thought we were about to hit a big jackpot,” says Mr Chen. Now, with Mr Cui the campaigner back in the spotlight, Mr Chen may have to wait longer.

Government scientists keep trying to make a case for GM food crops. But sometimes the government itself fails to speak with one voice. A feud erupted in October in the pages of two important state-run newspapers. One, the official newspaper of the Ministry of Science and Technology, scathingly rebutted a report in a provincial newspaper, Heilongjiang Daily, which quoted a soyabean-industry lobbyist as saying China’s leading researchers had concluded that GM soyabeans were unsafe. This, said Science and Technology Daily, was “seriously misleading”. It said the article had crossed a “moral and legal red line”.

Officials tend to keep quiet about how dependent China already is on imported GM soyabeans for its animal feed and food oil. The trade war will reduce its purchases of them from America. But China is expected to make up for that by boosting imports of beans, mostly GM ones, from other countries such as Brazil. “What scientists should be saying is that if we had done things differently ten or 15 years ago, we would not be in this situation” of having to rely on foreign supplies, says Mr Cao, the University of Nottingham academic. China could have boosted its own production of the vital crop by growing its own GM beans. “Even if we do start now, it will take us years to catch up,” he says.

How different it could have been. In 1992, when China allowed the commercial production of virus-resistant tobacco plants, it was the first country in the world to do so with any GM crop. Officials once touted goals of growing the majority of the country’s rice, wheat and maize using GM strains by 2010. Now even the more modest target set in the latest five-year tech plan is in doubt. If China is to start commercial growing of GM maize by 2020, it will need to have plans in place and seed stocks ready by next year. Mr Chen is not entirely confident it will. He is hedging his bets by developing other agri-technologies: “The government is just waiting and waiting, and I can’t wait forever.”