Libya’s feuds cross the Mediterranean

FOR ONCE Italy’s populist government will be pleased to see a group of Africans cross the Mediterranean. On November 12th the leaders of Libya’s warring factions will gather in Palermo, the capital of Sicily, for a two-day peace conference.

Italy has an interest in bringing order to its former colony. Libya is an important source of fossil fuels. Its Greenstream pipeline carries gas from western Libya to Sicily. Less welcome are the 647,000 migrants who are thought to have crossed the Mediterranean to Italy since 2014. Most set off from Libya. Their numbers have recently plummeted—just 22,000 arrived in the first ten months of this year, an 80% drop from last year. But they still rile Matteo Salvini, Italy’s de facto leader.

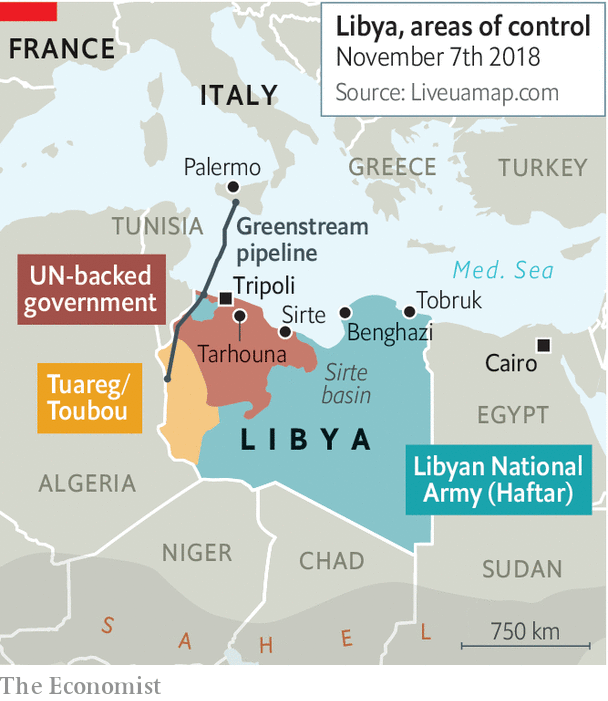

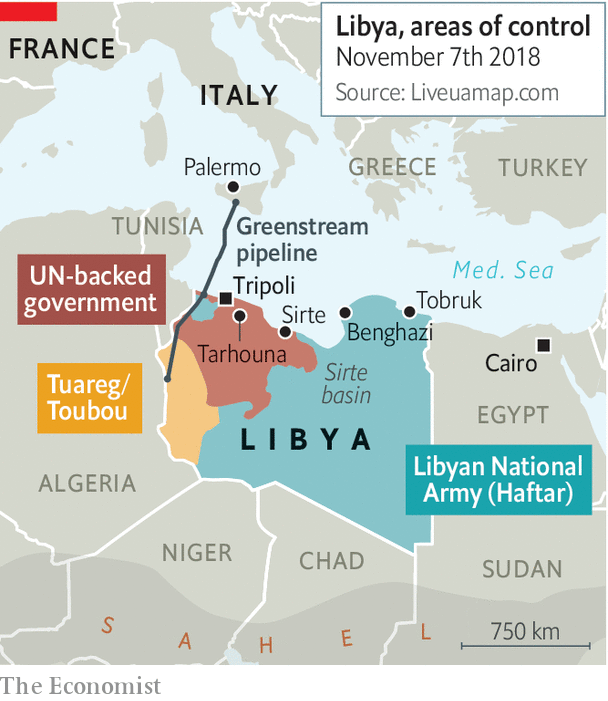

Mr Salvini will have his work cut out. The situation in Libya is bleak, with the country split between rival militias and UN-led peace talks bogged down. One of the dignitaries in Palermo will be Fayez al-Serraj, head of the UN-backed government. Despite his lofty title, in practice he is little more than the mayor of Tripoli, the capital, which he controls only with the help of allied militias. One of them, from the nearby town of Tarhouna, attacked Tripoli in August over an economic dispute. More than 100 people were killed before the UN negotiated a ceasefire.

Things are little better in the east, ruled by a general-turned-warlord called Khalifa Haftar. Islamist militants still carry out car-bombings and assassinations, while General Haftar undermines state institutions in Tripoli. He controls the strip of coast near Sirte, where Libya’s main oil terminals are located (see map). They are meant to be operated by the Tripoli-based National Oil Corporation. In June, however, the general’s men seized them and announced that revenues would be sent to a rival oil corporation in the east. They withdrew only after America threatened to impose sanctions. In the south, meanwhile, ethnic Tuareg and Toubou militias are battling for control, and criminal gangs from neighbouring Chad prey on civilians.

So, to put it mildly, things in Libya are not conducive to a peace conference—but Italy is more concerned with the situation in France. Both countries are jockeying for influence. Italy’s interests lie in western Libya, where both the gas pipeline and the migrant boats enter the Mediterranean. It sees Mr Serraj as an ally and has reportedly paid western warlords to stop migrant boats from setting sail. France is happier to work with General Haftar, whom it sees as more likely to stabilise the country. The French army has deployed thousands of its troops to fight jihadists in five former colonies in the adjacent Sahel region.

In May France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, hosted the Libyan rivals for his own summit. They agreed to hold elections by December 10th. That deadline was always delusional—even ignoring the violence, Libya lacks an electoral law. It also undermined the UN envoy, Ghassan Salamé, who wants Libyans to hold a national conference and draft a new constitution before holding elections.

Both Italy and France have commercial motives as well. Libyan oil is cheap to extract and easy to export to Europe. Eni and Total, the Italian and French energy giants, have long competed to produce it. Eni is the largest foreign producer in Libya, but Total is starting to catch up. In March it acquired a 16% stake in the Waha concession in the Sirte basin. If the deal goes through, it could produce 400,000 barrels per day in two or three years. Eni’s CEO, Claudio Descalzi, says he welcomes the “healthy” competition. “[Libya] benefits from this,” he says. The Italian government is less sanguine. It resents French involvement in a country that it sees as in its sphere of influence. Italian politicians accuse Mr Macron of helping General Haftar for Total’s sake.

Other foreign powers are pushing their interests in Libya, too. Egypt and the United Arab Emirates have given military support to General Haftar, whom they view as an ally in their fight against political Islam. Russia, eager to expand its influence, has hosted the general in Moscow, treating him like a head of state. Now Mr Macron and Mr Salvini are using Libya as part of their own competition for leadership in Europe. The UN-led process has been agonisingly slow. But it remains the closest thing Libya has to a way forward.