Vietnam is getting old before it gets rich

AS DAWN BREAKS in Hanoi the botanical gardens start to fill up. Hundreds of old people come every morning to exercise before the tropical heat makes sport unbearable. Groups of fitness enthusiasts proliferate. Elderly ladies in floral silks do tai chi in a courtyard. In the shade of a tall tree, dozens of ballroom dancers sway to samba music. Others work up a sweat on an outdoor exercise-machine. Tho, an 83-year-old with a neat white moustache, says he comes to walk round the lake every day, rain or shine.

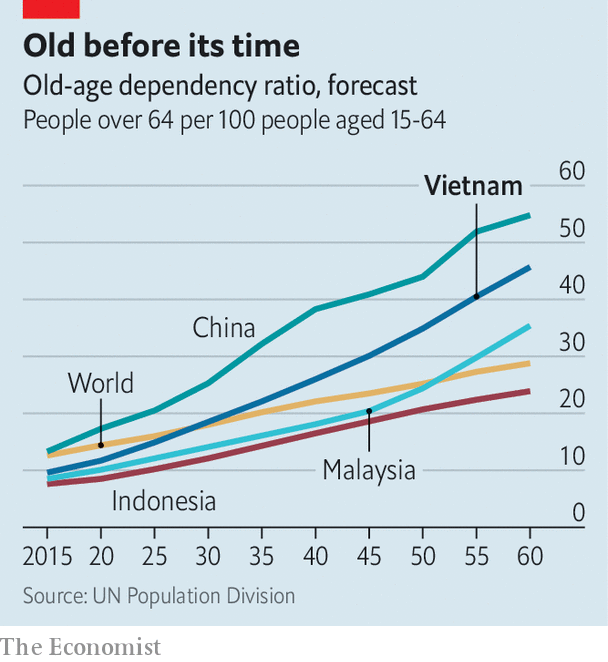

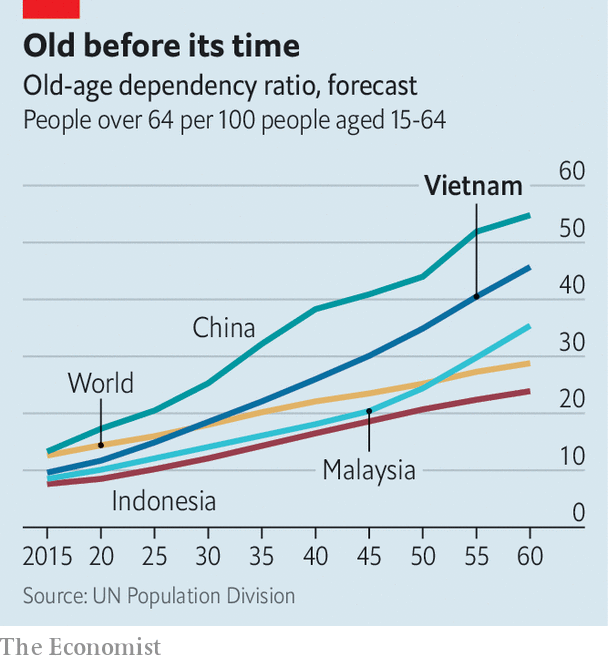

In the next few decades the gardens will become busier still. Vietnam has a median age of only 26. But it is greying fast. Over-60s make up 12% of the population, a share that is forecast to jump to 21% by 2040, one of the quickest increases in the world (see chart). That is partly because life expectancy has increased from 60 years in 1970 to 76 today, thanks to rising incomes. Growing prosperity has also helped bring down the fertility rate in the same period from about seven children per woman to less than two. In the 1980s the ruling Communist Party started to enforce a one-child policy. Though less strict than China’s, it has hastened the decline.

Demography is changing in similar ways in many Asian countries. But in Vietnam it is happening while the country is still poor. When the share of the population of working age climbed to its highest in South Korea and Japan, annual GDP per person (in real terms, adjusted for purchasing power) stood at $32,585 and $31,718 respectively. Even China managed to reach $9,526. In Vietnam, which hit the same peak in 2013, incomes averaged a mere $5,024. Indonesia and the Philippines are expected to reach the turning-point in the next few decades, with an income level several times higher than Vietnam’s.

This shift brings headaches. First, will the government be able to support millions more Vietnamese in old age? Only the extremely poor and people over 80 (together around 30% of the elderly) get a state pension, which can be as little as a few dollars a week. The most recent survey of the old, in 2011, found that 90% of them had no savings worth the name. Debt was common. Supporting them will become ever more expensive. The IMF predicts that pension costs, at the present rate, could raise government spending as a share of GDP by eight percentage points by 2050. That is faster than in any of the other 12 Asian countries it examined.

The problem is worse in the countryside, where most old folk live. Previously the young cared for their parents in old age. Today they tend to abandon village life to seek their fortune in the city. Surveys suggest that the share of old people living alone is rising, especially in villages. Many work until they die. Around 40% of rural men are still toiling at 75, twice the rate of city-dwellers. In Britain that figure is 3%. Often they do gruelling manual jobs, such as rice farming or fishing.

Providing health care for millions more old people is another worry. Alzheimer’s, heart disease and age-related disability are growing. In the botanical garden Toau, a 78-year-old in a white sports T-shirt, says he is there on doctor’s orders, before taking a pill for his bad heart and joining an exercise group. About a third of over-60s do not have health insurance, which is costly. Many provinces still have no proper geriatric departments in hospitals. Informal health-insurance groups have popped up to fill the gaps. For a fee, members get exercise classes and free check-ups. But few doctors are trained or equipped to treat more serious conditions.

The government is starting to implement policies to reduce the fiscal burden and improve the lot of the elderly. Last year it relaxed the one-child policy. In May it said it would increase the retirement age from 55 to 60 for men and 60 to 62 for women, and reform the pension scheme to provide wider coverage. Next year it plans to begin revamping the health-insurance and social-assistance systems.

But none of that will change the structure of the economy. Usually as countries climb the income ladder they shift from farming to more productive sectors, like services. By this yardstick, Vietnam is lagging behind its neighbours. When the working-age population peaked in 2013, agriculture accounted for 18% of the economy. At the same juncture in China, agriculture was just 10% of GDP. Worse, farmers’ output tends to decline with age, unlike, say, that of managers. This over-reliance on agriculture partly explains why three-quarters of Vietnam’s workers are in jobs where they become less productive as they get older. In Malaysia that is the case for only about half the labour force.

Boosting productivity will be tricky. The government is still wedded to statism. State-owned enterprises dominate many industries. Most university students, meanwhile, waste at least a year learning Marxist and Leninist theory. Many countries in Asia are ageing fast. But growing old before it becomes rich makes Vietnam’s problems all the greater.