Sanctions on Eritrea are lifted

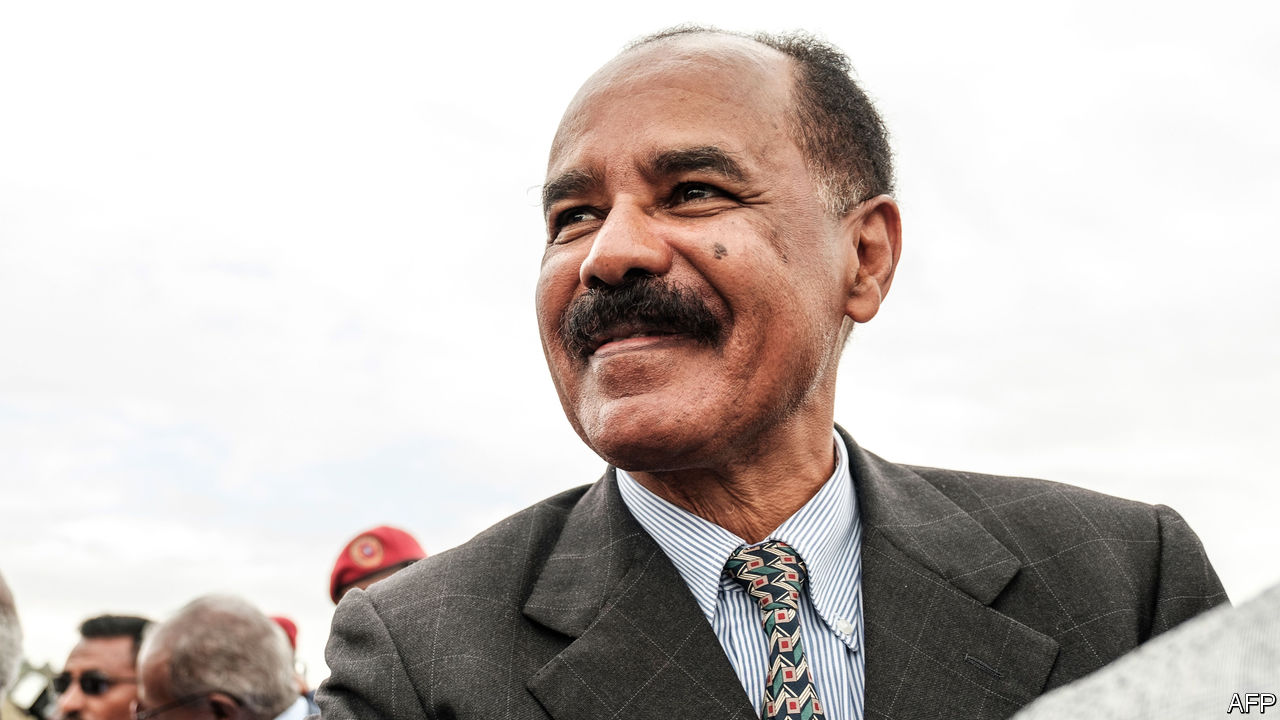

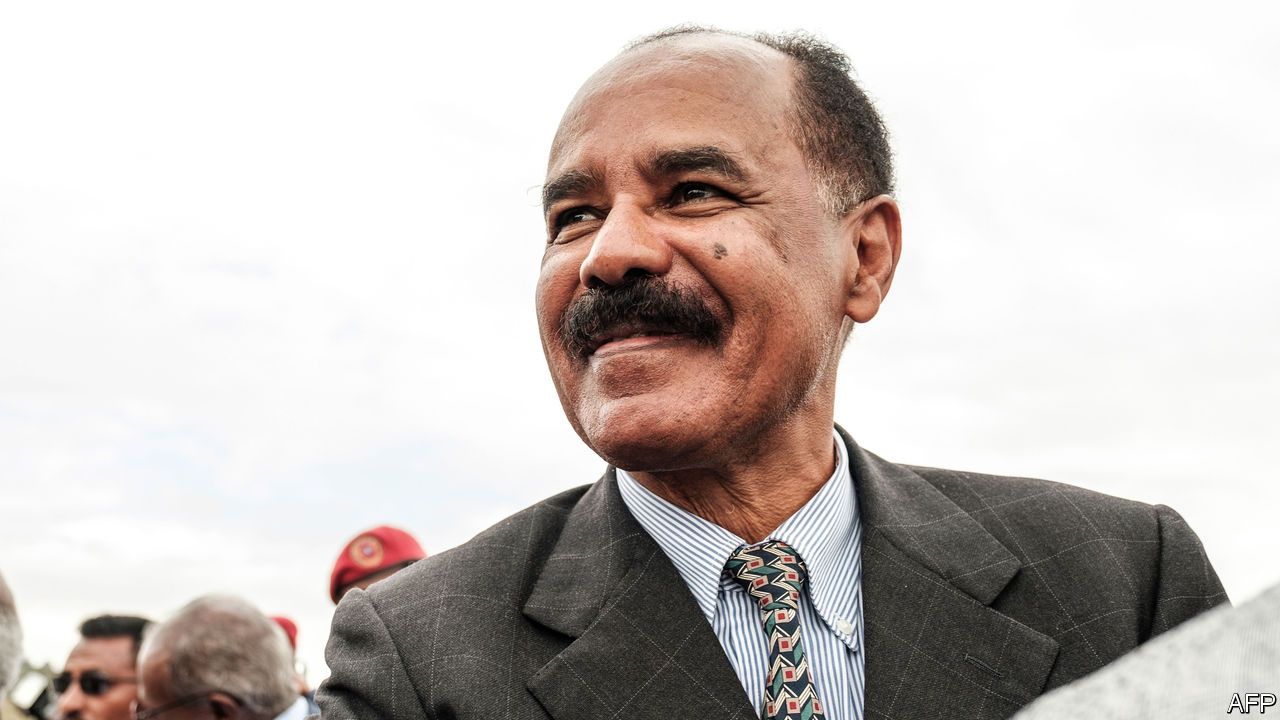

ERITREA HAD AN inauspicious start to the year. In January neighbouring Sudan accused it of supporting armed rebel groups and closed its border. Eritrea responded by alleging that Sudan, along with Ethiopia and Qatar, was plotting to overthrow its president, Isaias Afwerki (pictured). Meanwhile, relations with Ethiopia, another neighbour, with whom it fought a bloody war between 1998 and 2000, were stuck in a deep freeze. A UN arms embargo, imposed in 2009, in part over its alleged support for jihadists in neighbouring Somalia, remained in place. Eritrea was Africa’s most isolated dictatorship.

Then everything changed. In July Isaias signed a peace deal with Ethiopia’s new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, leading to a resumption of relations and an opening of their border. Weeks later Eritrea agreed to restore diplomatic ties with Somalia, after 15 years of animosity, and made progress towards resolving a long-standing border dispute with Djibouti. Last month it was reported that Eritrea and Sudan might also make up. “We are now entering a new era,” said Isaias. Indeed, on November 14th the UN Security Council voted unanimously to lift the arms embargo and the threat of targeted sanctions on Eritrean officials.

The move by the UN seemed unlikely a year ago. Eritrea had blocked the UN’s investigators from examining the country’s ties to foreign rebel groups and suspected violations of the arms embargo. Observers assumed that greater co-operation, and a full rapprochement with Djibouti, would have to precede the lifting of sanctions. Some Western countries also wanted to see improvements in Eritrea’s woeful human-rights record. “Eritrea cannot assume that by saying wonderful things and opening good relations with the neighbours that will automatically lead to sanctions relief,” said Tibor Nagy, America’s top diplomat for Africa, in September. But Somalia and Ethiopia, which has a seat on the Security Council, helped to persuade members to lift the sanctions.

They were not very effective anyway. Arms had been getting in to Eritrea, many smuggled across the border with Sudan. The expansion of a military base in Eritrea belonging to the United Arab Emirates is also thought to have violated the embargo. Eritrea was not under an economic blockade, nor were its officials’ assets frozen. In the mining sector, a big part of Eritrea’s economy, investment actually increased after 2009. The economic sanctions were so narrowly targeted they were “practically toothless”, says Awet Weldemichael of Queen’s University in Canada.

The sanctions may have deterred some foreign investment, but the government’s own policies are most responsible for Eritrea’s woes. The UN likened its system of indefinite conscription to mass enslavement. Foreign firms saw this as a litigation risk. Nevsun, a Canadian mining firm and one of the only big foreign investors in Eritrea, says sanctions have had “no impact” on its work—but it has been taken to court for allegedly using forced labour in the construction of its zinc and copper mine near Asmara, the capital.

The government runs a command economy, making decisions that deliberately “limit the size of the pie”, says Jason Mosley of Chatham House, a think tank in London. In the early 2000s the government started withdrawing business and import licences from Eritrean entrepreneurs, prompting an exodus. The Red Sea Corporation, a conglomerate owned by the ruling party, has a virtual monopoly on public contracts. Since 2006 there has been a total ban on private construction.

Eritrea’s improved relations with its neighbours have raised hopes of a more stable Horn of Africa. But the lifting of sanctions will do little to help ordinary Eritreans. Isaias has ruled the country with an iron fist since independence from Ethiopia in 1993. At the least, he will no longer be able to blame foreign powers for his country’s problems.