China is struggling to explain Xi Jinping Thought

THE INSTITUTE of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era occupies several rooms in the Marxism department of Renmin University in north Beijing. Qin Xuan, the institute’s director, says it is one of ten similar centres for the study of the philosophy that is attributed to China’s president. The institute has only a small administrative staff but about 70 affiliated academics. It produces research, offers advice to policymakers and organises seminars.

Mr Qin says that part of his team’s job is to explain Xi Thought to journalists, foreign diplomats and Chinese youngsters. In October he and researchers at other such institutes, all founded in the past year, appeared as judges and commentators on a youth-targeted game-show called “Studying the New Era”. It involved students who stood on the bridge of a starship and answered questions, posed by an animated robot, about Mr Xi’s speeches and biography. The show was part of an unusually lively series of programmes about ideology called “Socialism is Kind of Cool”, produced by a provincial television station.

A year has passed since Mr Xi, at a five-yearly Communist Party congress, declared that China had entered a “new era” and outlined how the party should manage this. The congress gave its rubber-stamp approval and revised the party’s charter to enshrine Mr Xi’s thinking on the topic as one of its guiding ideologies (he and Mao are the only ones named in the document as having Thought with a capital T—a mere Theory is ascribed to Deng Xiaoping).

Since Mr Xi took power six years ago, his aim has been fairly clear: to boost the party’s control over China’s fast-changing society while enhancing the country’s influence globally. But his Thought is woolly: a hodgepodge of Dengist and Maoist terminology combined with mostly vague ideas on topics ranging from the environment (making China “beautiful”) to building a “world-class” army.

Cartographic contortions

Xi Thought is now being “hammered home harder” than any set of ideas since Deng launched his “reform and opening” policy nearly 40 years ago, says Kerry Brown of King’s College, London. Most universities have incorporated lectures on the topic into the basic-level ideology courses which all Chinese students are required to take. Some have created additional elective courses for undergraduates. This academic year high schools have been supplied with new materials to help them teach it, too.

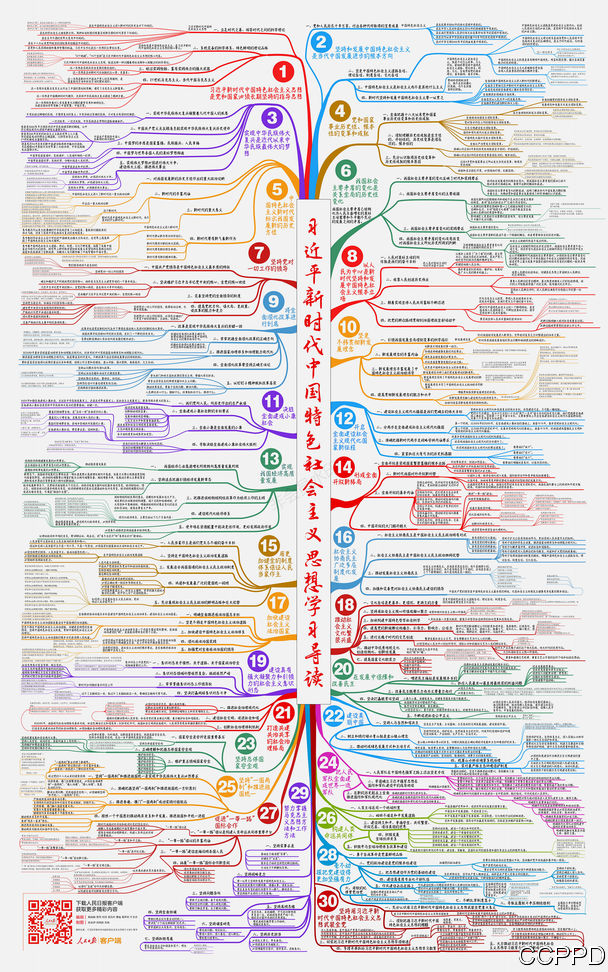

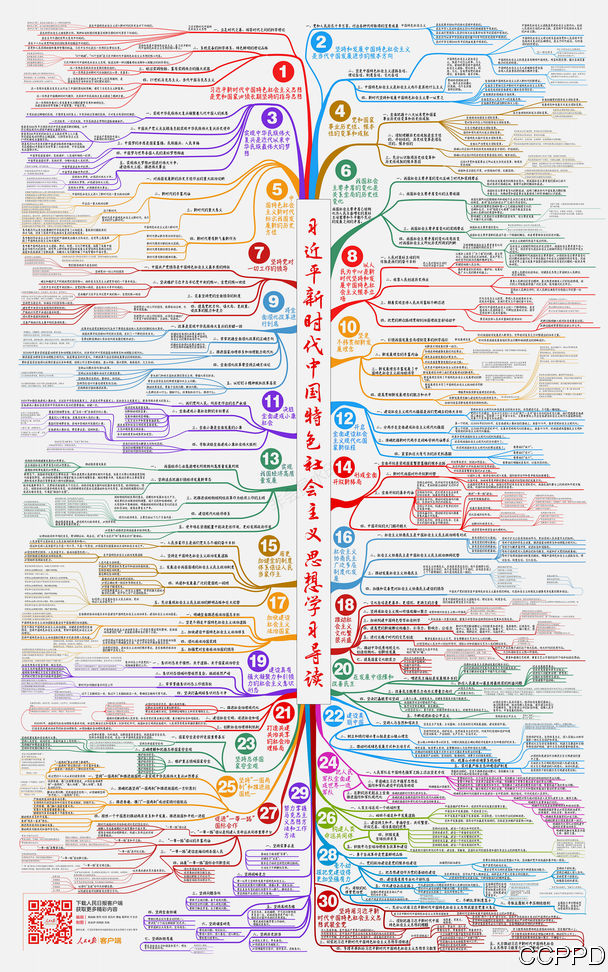

The indoctrination effort extends well beyond academia. In May the party’s propaganda department published a 355-page, 30-chapter book which it said provided an “in-depth” understanding of Xi Thought. It said every party cell must study the work. Last month the party’s mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, published on social media a labyrinthine mind-map based on the book (for a high-resolution image of this map, see economist.com/xismind). It is so packed with ideas and quotations that much image-expanding effort, as users complained, is required to make it legible. The map’s complexity conveys the ordeal that those trying to master the Thought are facing.

To help them, some big firms have set up Xi Thought “study rooms”. So too have libraries and community centres. In July Global Times, a tabloid owned by the People’s Daily, crowed that the Thought was being “studied in all corners of society, from local governments to media outlets, from university students to street cleaners”.

One purpose appears to be to enhance Mr Xi’s stature as a leader comparable in power to Mao. Deng Theory is less often mentioned these days. Last month Mr Xi made his first publicised trip in six years to Guangdong, the southern province where many of Deng’s reforms first took hold. During his tour Mr Xi did not even mention the architect of those reforms—a striking omission given that next month China will mark the 40th anniversary of their launch.

In April Qian Xian, a party journal, said there had been continual debate over the meaning of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, the concept at the heart of Deng Theory. In an apparent dig at a weakness of the Theory, the article said “some people” thought the phrase was another way of saying “capitalism with Chinese characteristics”. This, it said, had created “theoretical chaos”. Mr Xi stresses that socialism with Chinese characteristics is in fact about “socialism and not any other kind of –ism” (point two, subsection three on the mind-map).

Deep understanding is not required. The party has a long history of requiring people to mouth leaders’ slogans as a way of showing loyalty. Research on Xi Thought is mostly banal. Kevin Carrico of Macquarie University in Australia studied the Thought through a distance-learning course run by Tsinghua, one of China’s best universities. He wrote in Foreign Policy that the video lectures repeated platitudes that would be “familiar to anyone who has spent time in Beijing in the last 40 years”. They offered, he said, “an unprecedented opportunity to observe the poverty of China’s state-enforced ideology”.

Xi Thought is formally described as a summary of the “collective wisdom” of the party, and to some degree it is. In addition to borrowing from his predecessors, it is likely that Mr Xi relied heavily on the work of Wang Huning, a former academic who has played an important behind-the-scenes role in devising party-think since early this century, including Mr Xi’s notion of a “Chinese dream” (number three on the mind-map, with numerous subordinate points). Last year Mr Wang joined the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee, the pinnacle of party power.

Yet promoting Mr Xi as China’s thinker-in-chief could put him at risk. The more he is linked to China’s “new era” the harder it will be for him to deflect criticism for anything that goes wrong. A speech late last month by Deng Pufang, one of Deng’s sons, gave a hint of dissent within the elite. In it Mr Deng appeared to criticise Mr Xi’s assertive foreign policy. China, he said, should “keep a sober mind and know our own place”. That idea is not on the map.

For a high-resolution image of this map, see economist.com/xismind